The champion who never left: Olga Morozova’s five-decade reign in Queen's

Fifty-two years after lifting the trophy at Queen’s Club, Olga Morozova is back, older, wiser and ... still technically the defending champion.

Her 1973 win at the Rothman’s London Grass Court Championships came in the very first title match of the new WTA era. Armed with a wooden racquet and seeded eighth, the Moscow-born right-hander defeated No. 3 seed Evonne Goolagong 6-2, 6-3 to claim what remains arguably the biggest singles title of her career.

“It’s got to be some kind of record, right?” Morozova said with a mischievous glint, chuckling at the idea that her reign as Queen’s champion has quietly stretched across five decades.

For reasons that would soon become historic, Billie Jean King and Rosie Casals skipped singles that week -- they won the doubles instead -- but the singles draw was stacked. Margaret Court and Chris Evert led the 64-player field, and most of the world’s best showed up for what was, at the time, a key grass-court tune-up.

“I’m a tennis player, and a tennis player wants to win, so when you do you have good memories,” Morozova said during her return to Queen’s this week. “It doesn’t feel like it’s home, exactly, but it feels like something very nice.”

Now back on the calendar as the host of the HSBC Championships, a WTA 500 event, the Queen’s Club has long held a revered place in British tennis history. But in the 1970s, it was already showing strain from staging concurrent men’s and women’s tournaments. In 1974, the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) relocated the women’s event to Eastbourne, launching a hugely successful run on the south coast, but denying Morozova a chance to defend her title.

Some parts of Queen’s remain much as they were. The gabled row houses still peer over the grounds, and the temporary bleachers were packed even back then. The grass has always been impeccable.

Still, Morozova couldn’t help but marvel at how much has changed.

“The court with the old brick clubhouse feels the same, but the environment is really quite different,” she said. “It’s still traditional, and of course you have the beautiful grass, as it was when we played. But there are more crowds, and everything feels bigger and brighter with all the branding.”

Vindication on the grass

On a personal level, winning at Queen’s was deeply satisfying for Morozova, who felt it justified her No. 8 seeding at Wimbledon the following week. At that time, before computerized rankings, seedings were decided by committee and her high rating had raised a few eyebrows.

The context of her win was even more momentous, for it was during Queen’s week that King, supported by Casals and others, rallied more than 60 women players to a ride-or-die summit at the nearby Gloucester Hotel. At that meeting, the night before the semifinals at Queen’s, the WTA was born.

Attendance at the gathering was never really an option for Morozova. Five years into the Open Era, she continued to compete as an amateur under the thumb of the Soviet tennis federation -- the governing body dictated where she could play and kept her prize money but covered her travel and other expenses.

Morozova saw little of the £1,000 winner’s check she received for her Queen’s triumph (about £15,000 in today’s money), which was half the amount awarded to the men’s champion, Ilie Nastase. Morozova recalls staying at a dreary bed and breakfast in nearby Earls Court and catching the metro to the courts.

Even so, her passion for the game never dimmed and a few months ago she was delighted by a call from the LTA, asking whether she still had possession of the Queen’s trophy.

When it became clear the original was lost -- Morozova never took it home, nor received a replica -- the governing body of British tennis set about commissioning a new trophy and Morozova was asked to join the committee that helped settle on its design.

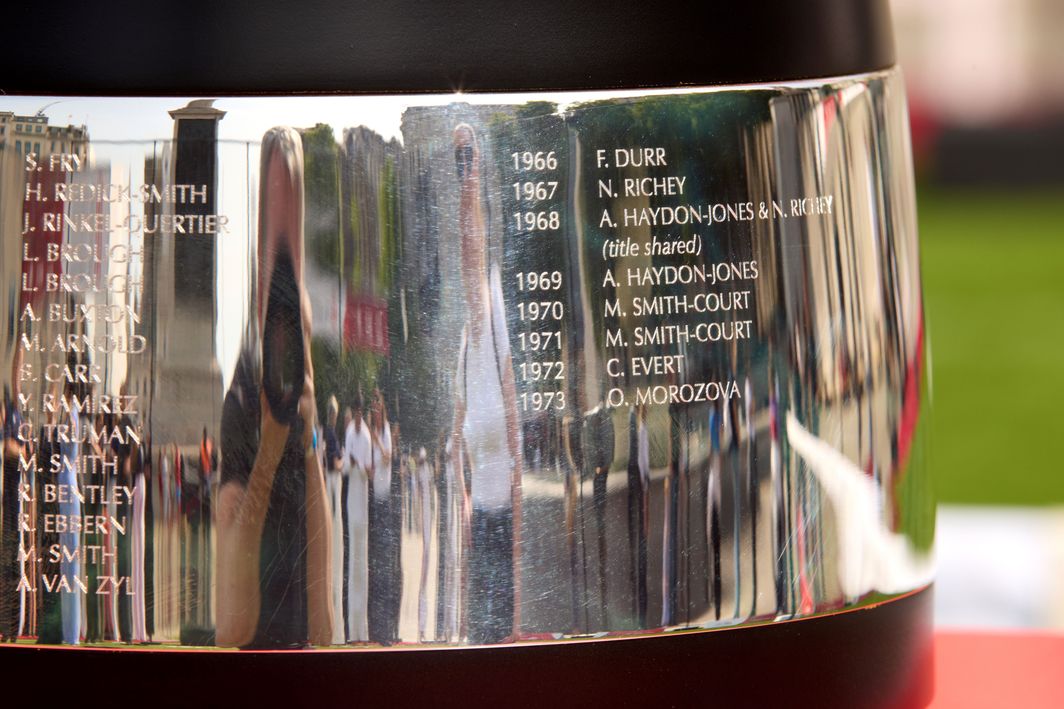

Creating a sense of continuation, the names of all former champions are engraved on the sleek new prize -- illustrious figures like Francoise Dürr, Ann Haydon-Jones, Nancy Richey, Court and Evert, who defeated Morozova in the finals at both Roland Garros and Wimbledon in 1974, even as they paired up to capture the doubles in Paris.

“It’s a new design for a new generation,” Morozova said. “But luckily, with a few good names on there, to start with!”

Far from being lost in nostalgia, Morozova, now 76 and a grandmother, celebrates the growth of the women’s game since her heyday. This year, total women’s prize money at the Queen’s exceeds £1 million and the LTA has plans to match the men’s purse by 2029.

“Women’s tennis is obviously much, much bigger now -- all around the world,” she said. “There are so many tournaments now for the ladies, and for the juniors too. Different countries every week, which makes us stronger. We’re getting more and more talent into the game and it’s very interesting.”

An inspirational figure for generations of players from the old Eastern bloc, Morozova has certainly played her part in this evolution. Aside from being the first Russian to win a Grand Slam title of any kind, her contribution as a tennis coach has been significant -- in the country of her birth (proteges include Elena Dementieva and Svetlana Kuznetsova) as well as the U.K, her home for the past three decades.

In addition to building her family life in the London area, Morozova was hired by the LTA to ramp up its junior program and worked with an array of British players, including Laura Robson, who is now tournament director of the HSBC Championships.

Rebels with a cause

On Monday, Morozova basked in the glow of shared legacy as she waved to fans from a balcony overlooking the newly-renamed Andy Murray Arena.

She was joined by Britain’s Christine Truman Janes, who won Queen’s in 1960, a year after capturing Roland Garros at 17, and Ingrid Löfdahl Bentzer, a former Top 15 player who was a member of the first WTA Player Council.

“I’m not often on the tennis scene these days, but it’s so lovely to be back to see old friends and reflect that, yes, I was a part of all this,” Janes said. “We played so long ago but all this is just wonderful to see.”

Swedish player Löfdahl Bentzer, who faced Evonne Goolagong at Queen’s in 1973 and later settled in London herself, echoed the sentiment. While she noted how different the sport was then, she said those years were unforgettable, not just for tennis, but for everything swirling around it.

“The women’s movement, race politics, music … it seemed like everywhere, society was changing,” she said.

She recalled a moment of uncertainty during the early days of the tour. “An abiding memory of the meeting at the Gloucester was that we were afraid we wouldn’t have enough players subscribing to our ideas, and Billie Jean famously had Betty Stöve minding the door so people wouldn’t leave,” she said.

Bentzer also reflected on how much was at stake: the limits placed by national federations, the lack of player autonomy, and the courage it took to break away.

“Our livelihoods and futures were on the line, and the creation of the WTA that week in London gave us strength in unity.”

More than 50 years later, the tour’s return to west London felt like a full-circle moment.

“I know the tickets are nearly sold out,” Morozova said. “It’s organized incredibly well. The players will love to play on this beautiful grass before Wimbledon, in London. Everywhere you look, from the hospitality to the dressing rooms to the practice courts, is done on a very high level. It’s everything you’d dream of.”